No Failure Is a Waste of Time

You can’t know the right words for your story until you’ve been living in it for awhile

I am in a hurry.

No, not right now. Today I have plenty of time.

But in general. I talk fast, I walk fast, I drive fast, and what patience I have for slowing things down has been developed over decades as a teacher and is in no way inborn.

As far back as second grade when my dad taught me long division, I used to do long, convoluted math problems in my spare time. Eventually I minored in math, and I took at least one math class every semester I was in college. Call me a masochist, but I loved a good multi-step problem with its pages-long solution. Still, because I don’t always have the greatest attention to detail, and I tend to rush (see above), I sometimes made mistakes.

And when I made a mistake on step 3 of a 21-step problem, it was never a simple fix. I had to go all the way back to step 3 and redo the entire problem - after, that is, I erased every embarrassing trace of my error. That was a delicate balance, too, rendering the pencil marks invisible while keeping the paper intact. It was all just a big waste of time.

The longer the problems were, the more important it became to just do the thing right the first time.

This is why I never understood the writing process. I know you’re checking the name of this newsletter now, wondering how I got to be a writer without possessing this basic knowledge. But there was just so much to it. Prewrite, draft, revise, edit. Why couldn’t I just know what I wanted to say and say it? If I could just pick the right words the first time, I wouldn’t have to waste all that time fixing it.

Surprisingly, I made it through all of k-12 and college, and I guess even grad school, with that attitude. I would proofread my papers to be sure the spelling and punctuation were okay, but in general whatever nonsense came into my head is what went down onto the paper and what got turned in.

That is part of why it took me four years to write my first book - because, during those early drafts, I agonized over the wording, “editing as I went.” (I put that in quotes because it wasn’t real editing I was doing.) I wanted to be sure to put the right words in the perfect order so I wouldn’t have to go back and change it later. In fact, when I went back for my first “editing pass,” I was already trying to optimize every single line. This is a big no-no, and I’ll tell you why.

All those agonizing words, and I bet you not a single one of them made it into the final draft. Should I say “In the morning, she went,” or “She went in the morning”? Turns out, neither. There’s always a better way to say things, but more importantly in those early stages, entire paragraphs, scenes, or even chapters can be cut to optimize the story and make the final product the best book it can be.

But why can’t I just write the right words the first time?

Because writing is all about exploration. In the beginning, especially of a book-length project, I write my way into the world. Despite my best attempts at preparing and outlining, I get to know the characters and world through writing them. It’s like the difference between how well I knew my husband on our first date (ooh, I still owe you a story about that, don’t I?!) and how well I know him now, 20 (*gulp*) years later. Or if I went to spend a few months Spain or Argentina while my Spanish was largely learned via Mexico and Puerto Rico. Eventually I’d adapt and be able to understand what was going on around me and speak more like a local, but it would take time as I learned about the world surrounding me.

A book is the same. You can’t know the right words for your story until you’ve been living in it for awhile.

There’s this scene that was in the novel up until the last last draft. It contained so much important information. It captured the mood of the book, the relationships between the characters, the setting where a lot of their lives take place. It was probably one of the oldest scenes in the book, come to think of it, going all the way back to Draft 1’s fever dream. I spent SO MUCH TIME on that scene. The writing was good. The imagery was great. But the scene was, well, kinda boring.

Well, let’s not say boring. Let’s say quiet. And this isn’t to say you can’t have a quiet scene or two in an 87,000-word book. But when that scene is standing between the reader and the big huge event that sets off the story, that’s not a good thing. Not for agents, anyway, who want to sell the most engaging book possible, and not for publishers who want people to actually buy the books they publish.

After much soul searching, I decided to cut the scene. I didn’t just slice it out and shred it, though. I moved it into a separate document and accounted for every single word of it. I highlighted paragraphs in different colors depending on which scene they’d best complement, and then I spliced this big, 3,500-word scene in bits and pieces throughout the story.

I also didn’t just copy and paste the exact same beautiful and agonizing words. I condensed them - paragraphs into sentences or even phrases in context where they could support the story without having to necessarily stand alone.

When my friend, Suzann, read the new opening, she had some words of comfort for me. “I’m sure it was painful to cut that scene, but you wouldn’t have been able to write the rest without it.”

As much as I wanted the perfect words the first time, what I really needed was to get to know the story and which of these details was important to its telling. The scene was more for me than for the reader, and while I was attached to it because of the amount of time I’d spent with it, now that I knew the story, I didn’t need it anymore.

So, was I wasting time writing all that, or all the other 200,000 words that didn’t make it into my 87,000-word book? No.* Just like the Garden of Failures, if I hadn’t “wasted all that time” learning from my gardening mistakes (You have to actually water them?! That explains some things.), I wouldn’t have this moderately successful garden this year, which has yielded us dozens of cucumbers, green beans, and tomatoes, along with some yummy peppers and (overripe or something) cantaloupes and possibly an eventual butternut squash come fall.

My failure to optimize hasn’t been a failure at all. I’ll be faster with my future books, but never, ever, will I get all the perfect words in the correct order the first time around. And neither will you. And that’s okay.

Talk soon,

*Though I did waste a lot of time changing the order of words that I would never end up using, and I give that practice 0/5 stars. Do not recommend.

P.S. I feel like a walking cliché a lot of the time writing this newsletter, but I hope you can, from my stories, look past that and recognize the reality to these trite sayings. I wouldn’t say them if they weren’t true!

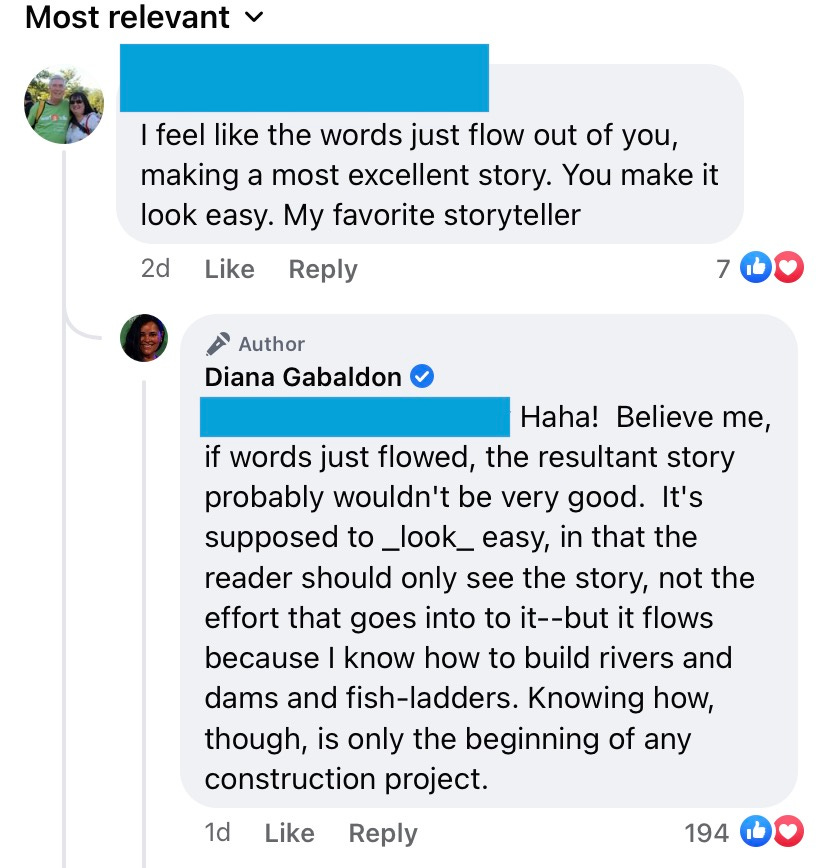

P.P.S. My friend shared this with me, just in time for the newsletter, and it’s super relevant. Diana Gabaldon is the author of the Outlander series.